Sacred Infrastructure

Notes from Hijazi Arabia

Muhammad Iqbal’s Shikwa ends with a couplet that puzzled me when I first read it as an undergrad:

The wine-jar may be Persian, but my wine is of Hijaz

The melody may be Indian, but my tune is of Hijaz.

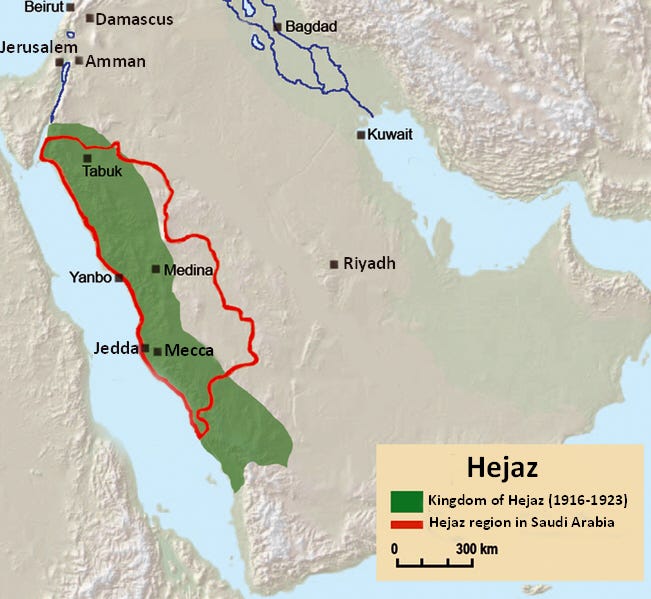

What is this Hijaz? I learned that it referred to a historical region of the western Arabian Peninsula, encompassing Islam’s holiest cities, Mecca and Medina, and the port city of Jeddah. But growing up, I had no imagination for it as a place with its own character. I only knew the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Hijaz meant nothing to me, and I wasn’t sure what it could have meant to Iqbal in 1909 that Saudi Arabia in 2019 did not.

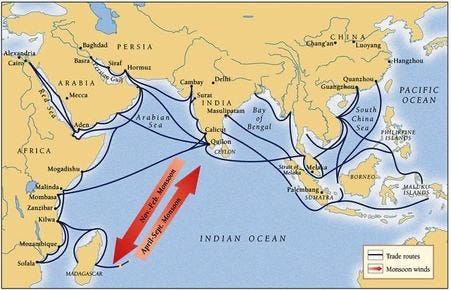

But now, with Silicon Valley eyes, I see the Hijaz more as a system optimized for throughput.1 The Hijaz region is shaped more by the movements of material goods—pilgrims, goods, disease. Long before oil or the modern Saudi state, the region functioned as a logistical interface between the Indian Ocean and the wider world beyond it.

Modernity arrived early in the Hijaz, with people and goods brought in via the latest technology and policy innovations. In the mid-19th century, Jeddah, halfway between Suez and Aden, became a critical node for steamships heading out of the Red Sea toward India and East Asia. Repeated cholera outbreaks linked to the Hajj forced imperial governments to intervene, prompting quarantine regimes and permanent diplomatic presences in the city. By the early twentieth century, many pilgrims arrived carrying passports. In 1937, the first commercial flight transporting Hajj pilgrims landed in Jeddah from Egypt. The pilgrimage scaled, and the systems around it scaled in response.

Modern Saudi Arabia is a project of the Najd, the interior, desert region of the Arabian Peninsula. The House of Saud consolidated power over the Arabian Peninsula by overlaying its tribal warfare with religious legitimacy gained by an alliance with the puritanical cleric Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahab. For a time, the Hijaz retained its cosmopolitan, commercial character, in part because Hijazi trade revenue was indispensable to the early Saudi state. Oil changed that balance. When oil rents began flowing directly to Riyadh, Hijazi elites lost their leverage, and the Saudi state moved to remake the region in the image of the insular Najd.

We landed in Jeddah late at night. We were visiting the Hijaz to perform Umrah, the lesser pilgrimage, which can be done anytime in the year (unlike the Hajj, which happens during a specified window). Many of the Saudi immigration officials were women. I could feel the McKinsey touch: let visitors encounter working Saudi women at the first point of contact. I got an e-Visa from a kiosk that took some basic information and scanned my fingerprints.

Outside, we met Akbar, the driver we had hired to be with us for our entire trip. More on him later. We headed out toward Mecca.

Mecca

A sign along the highway marks the boundary where non-Muslims must exit. Dense, concrete storefronts give way to increasingly taller towers. There are cranes everywhere, the sound of jackhammers permeates the night. The first anomaly on the horizon is the clock tower, rising out of the Mecca Valley.

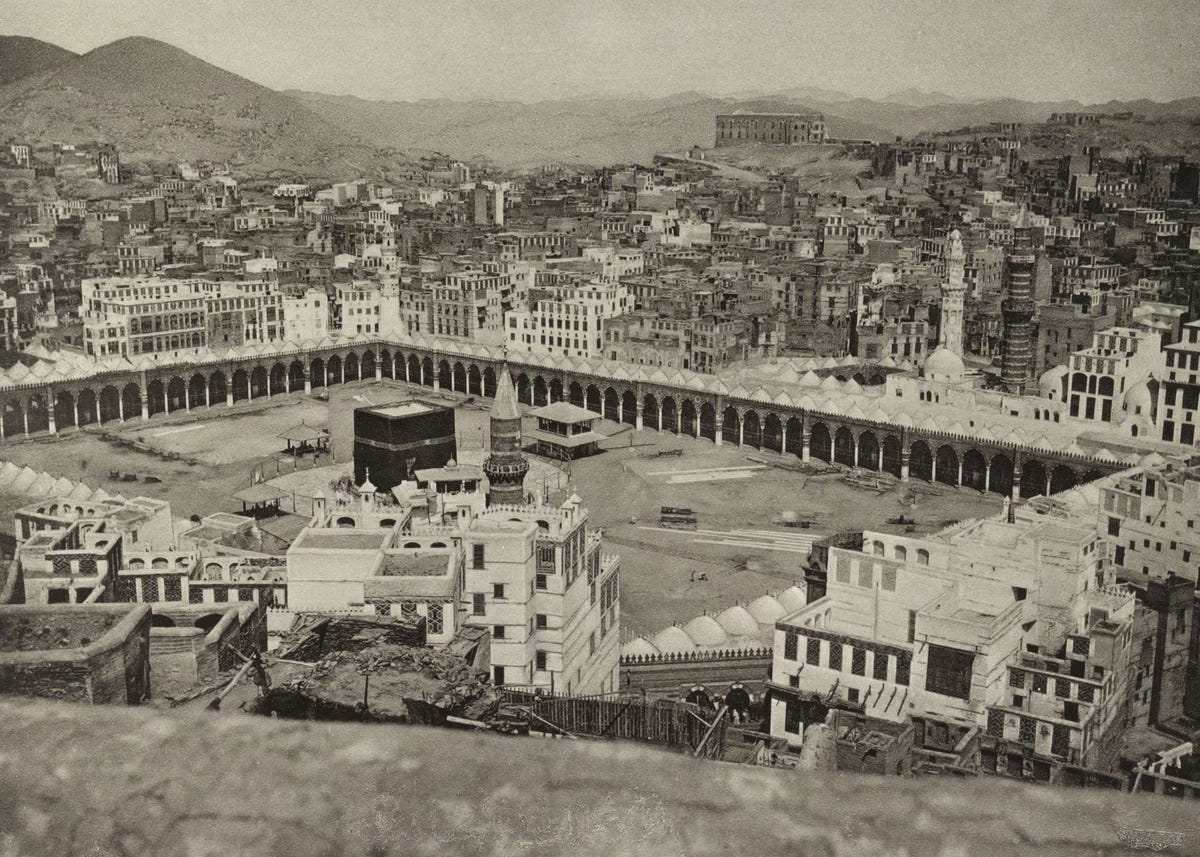

Mecca has been physically remade in the last few decades. Mountains and valley passes that once defined the city’s throughput have been flattened or tunneled through. Retaining walls separate new hotel complexes from older cement homes on the outskirt hillsides. Mecca today is a monument to modern civil engineering. Only the Kaaba, the black cube to which all Muslims face for their prayers, retains its original form from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, 1400 years ago. Everything else around the Kaaba is less than fifty years old and unlike anything that existed before it. The ever-expanding Grand Mosque and hotel complexes surrounding it are ultramodern, optimized by advanced analytics and modeling to maximize volume and flow. Oil revenues provided the material means, and Wahhabism’s hostility to shrines and monuments eliminated many of the trade-offs that plague heritage cities.

The Saudis have succeeded in expanding pilgrims’ access to Islam’s holiest site. The circumambulation courtyards and walkways around the Kaaba can handle 107,000 pilgrims per hour across its multiple levels. The entire mosque can hold more than 2 million worshippers, and the city has more hotel rooms than Las Vegas. When Booz Allen Hamilton tried to simulate crowd flow for a 2010 redesign competition, one day’s worth of pilgrim movement took two weeks to compute on a 16-core server.

Beyond the “Muslims Only Beyond this Point” sign on the highway to Mecca, nothing else filters visitors and worshippers out. No one gets asked to prove they are Muslim. No one gets asked to prove they are the “right” kind of Muslim, and Shias and Sunnis and Wahhabis and non-Wahhabis are welcomed alike. I heard dozens of languages, saw tour groups from places like Kazakhstan and Iran and Gambia. With such a diverse population, crowd management cannot be left to signage or implicit norms.

This all gets taken for granted. Sure, the Saudi projects are in part politically motivated, to assert the House of Saud’s legitimacy over Mecca and erase remnants of Ottoman control.2 And, sure, the mosque expansions and renovations are in part religiously motivated, to assert that austere, literalist, reading of Islam. And sure, the Mecca Clock Tower, one of the tallest buildings in the world, is an absolute eyesore. The clock tower absorbs all the aesthetic outrage, but obscures the more interesting story, of an ancient ritual now embedded in one of the most advanced crowd-management systems ever built.

The Grand Mosque is built for one main function: facilitate the movement of up to millions of worshippers around the Kaaba. Circumambulation around the Kaaba is a core pilgrimage rite, and pilgrims are doing it continuously, except during the five congregational prayers. There are many pretty mosques out there, but the Grand Mosque is not one of them. The exterior walls, of great grey granite and massive gates, have an almost Mordor-like seriousness and austerity. The mosque’s opulence is found in its design and amenities, not in its ornament. Everything inside is designed for facilitating the movement of hundreds of thousands of people daily.

Many times, I saw pilgrims hesitate at the tops of escalators, backing away, encountering them for the first time in their lives. This is one of the most expensive buildings on earth, hosting some of its least experienced travelers.

The crowd is managed by the physical layout of the building. A complex system of ramps, catwalks, and one-way walkways steer people between courtyards and prayer areas. Guards and ushers operate barriers dynamically, opening and closing routes into and out of the mosque depending on prayer times. At times, the guards are aggressive, yelling at worshippers who start praying in walkways or start forming lines for the congregational prayers too early, obstructing circumambulation. Once the guards close a gate, no amount of pleading, except for that of a lost child, will grant an exception.

The Grand Mosque is spotlessly clean. Hundreds of uniformed migrant workers ceaselessly sweep the floors. Another dedicated team replenishes water coolers placed throughout the mosque with water from the Zamzam well.

Worship in the Kaaba courtyard is not private and meditative. The constant motion and noise within the Kaaba courtyard demand physical awareness. The collective mass of people moves with a life of its own, and some pushing and shoving is inevitable. The men are all wearing two white, unstitched garments, one white garment short of a full burial shroud. I passed by pilgrims awestruck and I passed by pilgrims videocalling their friends. I weaved through organized groups chanting prayers collectively and bodies heaped in prayer alongside the walls of the Kaaba. Despite the expansion projects, this is the same shared intimacy that erased the prejudices of Malcolm X when he visited in 1964.

One of the stranger characteristics of the Grand Mosque (by strange I mean unfamiliar) is the lack of gender segregation. Pilgrimage rites are done with men and women in the same space, sometimes pushing up against each other in tight crowds. Often, I encountered contingents of heavyset Arab women, arms linked together, shoulders lowered, pushing through the masses to get closer to the Kaaba.

The Grand Mosque is one of the only places on earth today where you can experience monumental architecture in real time. Expansions are always ongoing. But because the mosque needs to remain operational, we get to see inside the construction site. Pillars in the great mosque do much more than hold up the ceiling. Now, they house air conditioning units, speakers, and security cameras.

Mecca has been big on commerce since the pre-Islamic era. Today, malls catering to all classes sit just outside the Grand Mosque, from dense, winding souks to modern open malls with familiar western brands. Merchants and customers and merchandise come from everywhere. My favorite interaction was with a Burmese salesman at an abaya shop. He was negotiating with my wife in Urdu and a group of Nigerian women in Hausa. He told us all he learned Hausa through TikTok. I got better prices if I haggled in Urdu than if in Arabic, regardless of the salesman’s native tongue.

Medina

On the road between Mecca and Medina, we were stopped at a police checkpoint. Akbar told the officer that we are his cousins and that he is giving us a friendly ride and that he is not a hired driver. The officer was not convinced by this story and gave Akbar a dismissive nod as he took photos of Akbar’s car. The officer checked our passports but asked us no questions and then waved us all through. Some 10 minutes later Akbar got a text on his phone telling him he was being fined 375 riyals (~$100) for driving as an unlicensed chauffeur.

Medina has better weather, and is palpably calmer. We visited the site of the Uhud Battlefield, where the nascent Islamic state faced its first existential threat. The total number of combatants on both sides is estimated to be under 4,000 people. The Prophet’s Mosque in Medina can hold more than 1 million worshippers. Visiting the battlefield, framed by the Mountain of Uhud and the smaller Mount Rumah gave me a sense for just how small the early Islamic state was.

The Prophet’s Mosque in Medina is beautiful, perhaps one of the most experientially stunning buildings I’ve been in. The exterior stones are a soft, beige-pink. Dozens of retractable canopies, like great umbrellas, mounted on marble columns, line the courtyard around the mosque. Step inside, and a forest of columns and arches. From the center, hundreds of arches and columns extend in all directions. Unlike the Grand Mosque of Mecca, the Prophet’s Mosque is designed as a place of respite. People are praying, people are napping, people are reading. Exhausted after the physical exertion of Mecca, I fell asleep on the carpet after the dusk prayer.

The forest of arches reminds me of what the Grand Mosque of Cordoba must have felt like, before the terrible 16th century Reconquista renovation inserted a baroque chapel into the center of the building. Unlike the Cordoba mosque’s double horseshoe arches, the Prophet’s mosque has pointed arches, reminiscent of Arab-Norman architecture I saw in Sicily.

The Prophet’s Mosque also retains older, Ottoman-era projects, including the iconic Green Dome that sits over the Prophet’s grave. The domes in the newer Saudi expansions are built on sliding rails, which open during the night to allow in air and close during the day to provide shade, inverting the original logic of a dome.

The Mosque’s giant retractable canopies draw considerable wonder from visitors, who gather to watch the umbrellas open and close at sunrise and sunset. The columns and canopies of the Prophet’s Mosque add in an element of spectacle absent from the Grand Mosque of Mecca.

Less crowd management is necessary here because the mosque functions more like a regular mosque, with no ritual circulation. The main exception is the Prophet’s tomb, where guards and barriers control the flow of men coming to pay respects. This is the most sincere crowd of men I have ever been a part of. Men of all ages and races and classes have tears in their eyes and prayers on their lips. An elderly man from Pakistan weeps as he takes photos with a Nokia phone from the 2000s. A Tunisian man records an influencer style video with his iPhone in a stabilizer. Ushers yell at visitors who linger too long and look like they are supplicating to the Prophet. Just outside, the mosque lies Jannat ul-Baqi, the resting place of many of the Prophet’s companions. Today, it is a flat plain, with small, plain stones as grave markers. The Saudis have removed all shrines and tombs and religious police actively break up groups that gather around known graves of famous companions. The religious police come off snootier than the guards, because they assume an ideological superiority and purity, whereas the guards are just trying to keep people moving.

The Wahhabis destroyed many other historic sites beyond shrines, such as preserved homes and military installations, basically anything not a mosque. On a previous visit, I hired a private guide who took us to unlabeled ruins and fenced off sites. But recently, some of the sites have been rehabilitated and listed as official heritage sites, in line with Saudi Arabia’s tourism initiatives. I visited the Well of Ghars, site of several stories from the life of the Prophet, which is now marked by a cute sign and fitted with a faucet for visitors to drink from.

Jeddah

We arrived in Jeddah late at night, exhausted. We were staying in a hotel on the Corniche, a seaside recreational and commercial area teeming with life. Families were picnicking on the boardwalk. Kids were biking and adults were rollerblading, a wide pedestrian boulevard, weaving between couples. Cafes and restaurants were clustered on the street parallel to the boulevard. We saw several cars driven by women, and one car full of women singing to Taylor Swift. Most people around us seemed Saudi. Unlike Makkah and Medina, where nearly all women covered their face, only about half the women were wearing veils. Some women were not wearing headscarves, some had their abayas open, billowing in the sea breeze. More than half the men were wearing crisp white thawbs. The commercial block had two lanes of drive through coffee and dessert shops that felt reminiscent of 1980s America. The coffee and matcha offerings were rich, but foodwise there didn’t seem to be much beyond fried fast food and generic shawarma shops. We found one brisket burger restaurant, with quite average food.

The next day we went to visit Balad, Jeddah’s historic district. Along the way, we learned a bit more about Akbar. He came to Jeddah from Pakistan 13 years ago, initially recruited as a construction worker. He then worked as a painter, then in rebar work, then at a warehouse. He described his employers as harsh, at times cruel. A colleague at his warehouse job taught him how to drive, starting out with reversing trucks into position. He eventually landed a job as a driver for Chinese company, where he drove around executives. Three years ago, he left that job and bought his own car. Through an informal network of Pakistani drivers and clients, he started working as a private driver, a job which gives him significantly more autonomy and much better working conditions. In whatever spare time he has, he plays cricket. He showed us videos of cricket tournaments he organizes in Pakistan, complete with local sponsors and prize money. He has three kids and a wife back in Pakistan, who he tries to see once a year.

Akbar said life in Saudi Arabia was getting worse for migrant workers. Salaries were getting cut but prices were going up. A roommate of his has been out of work for several months, losing his job to newer immigrants (he named Bengalis) who were willing to work for less. He said the safety situation had also deteriorated, and he told us about how he got mugged at knifepoint by three African men after giving them a ride.

We reached the Balad neighborhood, which we enjoyed more than we expected. The older Hijazi homes have these beautiful balconies encased in carved woodwork. It was early in the afternoon, so most of the stalls and shops were closed. But there were several cafes and art workshops open, which felt lively and organic. We saw some tourists and some groups of locals. We stopped inside one café where a young Levantine woman was describing her tatreez-generator app to two friends. Again, we had trouble finding food that wasn’t fried or shawarma. We wished we could have stayed to see the Balad in the evening, when the neighborhood comes to life.

Murals for MBS’s Vision2030 are plastered across Jeddah. Vision2030 feels like an attempt to replicate the success in transforming the pilgrimage experience in other segments of society.

On the way to the airport, we passed by a massive plain of flat, empty land in Jeddah. Akbar explained that these used to be neighborhoods and commercial areas home to many migrant communities, including a “mini Pakistan” neighborhood. People and businesses in those now demolished neighborhoods were pushed out into the suburbs of Jeddah. Some of the land was cleared years ago, but no redevelopment has begun here yet.

Over five days and three cities, I saw little that celebrated a common Islamic past. In Mecca, the Saudi crest crowns the skyline atop the clock tower. The infrastructure works so well that it erases its own contingency. From inside the Grand Mosque, it is easy to forget how vulnerable Saudi Arabia’s defense is, how fragile even its airspace remains. The machinery of the Hijaz is so totalizing, so effective and efficient, that it is difficult to imagine Islam’s holiest cities as anything but Saudi Arabia.

For the Hijaz in terms of identity, culture, and political imagination see: Cradle of Islam, Mai Yamani.

For a good representation of this line of thinking see Mahdi Chowdhury “Archives of Salt”.