The Wax and Wane of Greatest Common Factor Islam

A quiet revival in the Central New Jersey suburbs

Visits home during college breaks were usually disappointing. The suburbs of Central New Jersey seemed to be in perpetual stasis, always flaunting their predictability. The only changes I noticed were new fast food franchises and long-term storage facilities that spawned on Route 1.

But after Covid, this changed. On each visit home, my family had an itinerary of new halal restaurants to show me. There are now three Turkish restaurants within a 10-mile strip on Route 1, one with a grocery, one with an event hall, and the third that just expanded out of a shack. There are Yemeni coffee houses and Pakistani tea houses. A proliferation of fried chicken sandwich joints. Central NJ always had many halal restaurants and groceries, but those were mostly immigrant hustler operations, what Google Maps might tag as “no frills”. These new businesses were different. They weren’t just selling food— they were curating vibes, delivering an intentional social experience. Specialized and differentiated, they were products of cultural fermentation and participants in a mature ecosystem.

My most recent visit to New Jersey was this past Ramadan. What struck me this time was the dynamism of the mosque scene. Just as the community now expects more from restaurants than mere halal compliance, its spiritual expectations are evolving too. Mosques are becoming more distinct, more intentional, and in the best cases, more intellectually serious and spiritually ambitious.

Nothing that follows should be interpreted as a theological or jurisprudential argument. I am just tracing a cultural sketch, a constellation of sorts, by connecting data points that stand out to me.

“Greatest Common Factor” Islam

In the 1980s and 90s, Central Jersey’s nascent Muslim community coalesced to serve the needs of immigrants from across the Islamic world. This resulted in an Islamic practice that was undifferentiated and overly simplified—what I call Greatest Common Factor Islam. It settled for a convenient common practice of the basics but lacked the intellectual coherence necessary to address epistemic questions. Several forces were at play: the aggressive export of oil-funded Salafism from the Gulf, the general prioritization of practice over thought, and the community’s need for a baseline practice that could accommodate the diverse and varied practices of immigrants from across the Muslim world.

Most immigrants—doctors, engineers, and other professionals—took Islam as self‑evident. In their home countries, faith was ubiquitous, and God was taken for granted. They may have been devout, but most were not formally trained in theology or jurisprudence. They brought a patchwork understanding from their home countries but struggled to explain their faith in a way that made sense to kids steeped in secular society.

I attended a full-time Islamic school until eighth grade. I found their religious pedagogy frustrating. One simple example: across the Islamic world, the iqamah (a second call to prayer signaling the commencement of the prayer) is performed with minor variations. My middle school teacher flatly refused to accept any variations of the iqamah other than the version prevalent in her home country. She offered no explanation as to why her version was “more correct.” In situations like this and many more, I was left thinking there just was no explanation. As a kid raised in an educational system that prized reasoning and inquiry, Islam often felt like a set of inexplicable constraints and untethered abstractions. This is the essence of Greatest Common Factor Islam—it transmitted a uniform practice, but without any cohesive explanation for why.

As a kid raised in an educational system that prized reasoning and inquiry, Islam often felt like a set of inexplicable constraints and untethered abstractions. This is the essence of Greatest Common Factor Islam—it transmitted a uniform practice, but without any cohesive explanation for why.

This minimalism, when presented to kids immersed in secular epistemologies, made Islam feel less like a tradition and more like a set of arbitrary rules. And to some degree it was arbitrary—I learned a particular version of the iqamah only because it was the version my middle school teacher happened to know. While iqamah variations are a relatively minor issue, the same dynamic shaped far more significant debates. Instead of discussing the permissibility of specific practices belonging to certain traditions, such as the celebration of the Mawlid, the community defaulted to the greatest common factor. With the spread of Salafism’s simple austerity and absent a competing robust discursive framework, those who held the most conservative opinions got away with positioning themselves as the most pious people.

With the spread of Salafism’s simple austerity and absent a competing robust discursive framework, those who held the most conservative opinions got away with positioning themselves as the most pious people.

But this is changing with a maturing second generation that feels unsatisfied by Greatest Common Factor Islam. On my most recent visit, I spent time at three mosques nearest to my home. Each mosque offered a distinct experience. The Central Jersey Muslim community is quite integrated, yet each mosque had unmistakable differences in leadership, programming, and youth/young adult participation. And because it was Ramadan, the busiest time of year for the mosques, these differences were especially pronounced.

I was most surprised by a subset of young men [1], mostly Rutgers graduates, that are seeking out classical, knowledge-oriented Islamic lineages. In their pursuit of specificity, they reject Greatest Common Factor Islam. They reject the liberal, reformist Islam of the layman American preacher who encourages Muslims to “try to be good people and remember God while you do it”. And they also reject the Salafist strains of Islam, those low-hanging hardcore counterculture revivalist movements that claim a return to “authentic” Islam by discarding centuries of discursive Islamic tradition.[2] Instead, these young men commit to rigorous seminary studies in one of the four classical schools of jurisprudence, either full-time or alongside their professional careers. In an even bolder rebuke of modernist and revivalist currents (both being products of modernity), many also practice mystical Islam and are associated with centuries-old Sufi orders. This emergent class of American-raised but classically educated Muslims is rapidly growing. And as it grows, its members are remaking the institutions of Greatest Common Factor Islam, such as the Islamic school I—and many of them—attended.

Three Mosques, Three Experiences, One Community

To illustrate how these three mosques—all orthodox Sunni mosques in a 20-mile radius—have differentiated, I want to give a brief description of each mosque in turn. Naturally, any 300-word description of a complex community organization will sacrifice precision for color, and I encourage the reader to take the most charitable takeaways from my crude vignettes.

I. Islamic Society of Central Jersey (ISCJ)

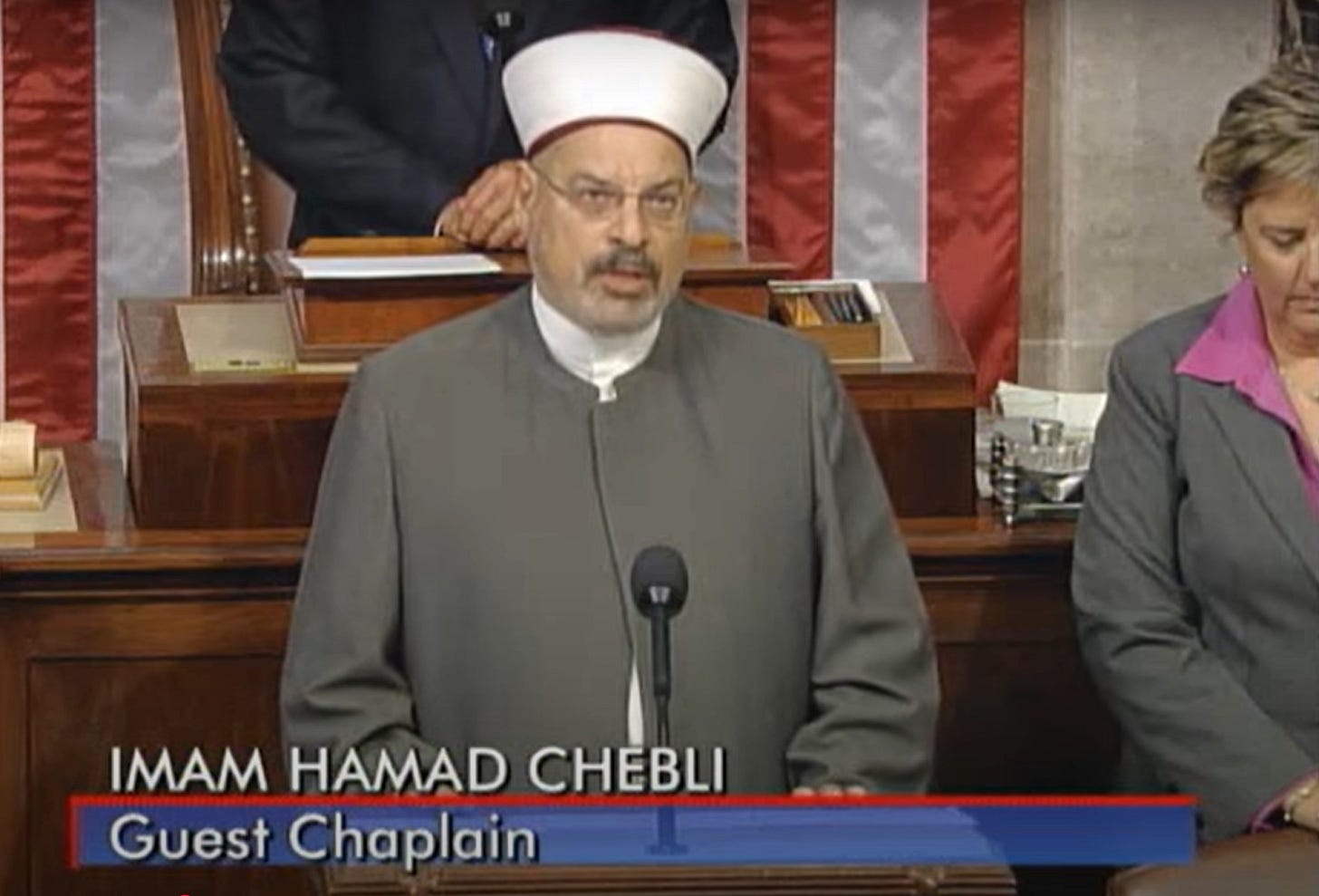

ISCJ is the first major mosque in Central NJ, founded in 1970 by Rutgers students. Its founders and subsequent leadership deserve great credit for establishing an institution that enabled fresh immigrant Muslims from around the world to form a community. ISCJ hosts the full-time Islamic school I attended, and that school is regarded as the best full-time Islamic school in the tri-state area. Alongside the full-time school, ISCJ’s distinguishing characteristic is its imam. Imam Hamad Chebli, a towering man approaching 6’5’’ with his turban, has been the imam—and the embodiment—of ISCJ for nearly forty years. His imposing figure and infinite approachability enable him to forge consensuses within the Muslim community and build needed bridges beyond it. Everyone in the ISCJ community has a story about Imam Chebli’s always effective and sometimes aggressive fundraising talents.

Over the last few years, ISCJ’s demographics have changed. I saw far fewer high schoolers and college students than when I was growing up. In the words of my friends who once went to ISCJ: “ISCJ fell off.” ISCJ’s relevance to the broader Central NJ community is carried by the reformed full-time Islamic school (more on that below). Imam Chebli is sought out as an established authority figure and mediator, not as an intellectual or spiritual guide.

I think of ISCJ like Starbucks—in the sense that Starbucks convinced the masses that coffee could be an artisanal product instead of utilitarian sludge, which served as the market foundation upon which specialty coffee took off. ISCJ reimagined the American mosque as a purpose-built home for a diverse group of Muslims, serving baseline spiritual needs alongside other community services. As the first native generation matured, they recognized the community’s segmented demand for differentiation. And ISCJ’s institutional inertia hindered its ability to adapt to an evolving community.

II. Muslim Center of Greater Princeton (MCGP)

About eight years ago, MCGP moved out of its rented office space and into its current building—a stunning, purpose-built mosque of exceptional beauty. A spectacular 30-foot tall mihrab structure, custom designed and imported from Turkey, stands as a testament to the community’s appetite for not just a place to gather, but a beautiful place to gather. I had my wedding ceremony in front of this mihrab.

MCGP is a mosque for the people, by the people. Nowhere is this ethos more apparent than in the parking lot. ISCJ hires private contractors to manage Ramadan traffic, but at MCGP, volunteers—many of them board members—don fluorescent vests and direct the flow. The same dynamic extends beyond logistics: the board members shape the spiritual orientation of the mosque, rather than a scholar or religious director designing programming based on a commitment to a defined tradition. MCGP’s approach to supplemental offerings somewhat resembles a platform model, where a variety of events associated with different traditions are available to the community.

At MCGP, it sometimes feels like there is more activity outside the prayer hall than inside it. After the weekly Friday prayers and nightly Ramadan prayers, the courtyard overflows with friends, vendors, and networkers. MCGP is a mosque that thrives on engagement. It’s the mosque to see and the mosque to be seen at.

III. New Brunswick Islamic Center (NBIC)

NBIC occupies a rented warehouse beside a discount furniture gallery. It’s a humble presence compared to ISCJ and MCGP. But inside, NBIC pulses with an intellectual intensity that has drawn followers far beyond Central Jersey.

The animating force behind NBIC is its religious director, Dr. Shadee Elmasry. A classically trained scholar and founder of Safina Society, Dr. Elmasry has built a platform that is both deeply traditional in pedagogy and innovative in distribution. Safina Society’s YouTube channel has over 100,000 subscribers, and its seminary initiative, Darul Fath, offers rigorous classical training in Maliki and Hanafi jurisprudence. He embodies an intellectual confidence and aesthetic fluency that makes traditional scholarship feel aspirational. His livestream captures a fusion of erudition and effortless cool that defines his appeal. For younger Muslims, he presents a living refutation of the false choice between religious devotion and cultural sophistication.

What most distinguishes NBIC, however, is its embrace of a specific lineage within Islamic mysticism. Dr. Elmasry and his students follow the Ba'Alawi tariqa, a Sufi order with deep roots in the Hadramawt region of present-day Yemen. This is not an abstract affinity—it is a living connection. Dr. Elmasry briefly studied in Yemen, and his PhD dissertation focused on a 17th-century Ba'Alawi scholar. Three of his students are currently enrolled full-time at Dar al-Mustafa, an internationally recognized seminary in Tarim, Yemen and the heartland of the Ba'Alawi tariqa. This past winter, a group of 17 men and 2 women from NBIC traveled for an intensive retreat in Tarim.[3] None of them are Yemeni, and almost all of them are academically distinguished STEM students, signaling that this revival is not about ethnic nostalgia, but the search for a coherent cosmological framework. Dr. Elmasry himself is New Jersey-born, of Egyptian descent. Yet through him, this tradition—far from Greatest Common Factor Islam—has taken root in Central Jersey.

An instragram post from Dar al-Mustafa featuring NBIC students during a winter retreat in Tarim, Yemen.

One Community: Balancing Inclusivity and Rigor

Central Jersey’s mosque landscape is as diverse as it is fluid. Congregants now choose from a menu of options, and while many individuals intermingle, institutional orientations persist.[4] The differences in the mosque orientations have led to the emergence of distinct subcultures. A superficial but illustrative example on headwear: At ISCJ and MCGP, I noticed some high school-age boys wearing checkered scarves—the ghutra of the Arabian Peninsula—in either an intentional signal of their affinity for Salafist Islam or perhaps in a more casual nod to the fashion of the present-day custodians of the two holiest mosques. But at NBIC, I saw dozens of men with colored Yemeni shawls draped over their shoulders, in expression of their affinity to the lineage of the Ba'Alawi tariqa.

Some mosques operate as funnels, aiming to include a broad swathe of Muslims, including those who might shy away from intense spiritual or intellectual exploration. Others function as filters, serving as institutional homes for those who demand more rigor. Rigor does not necessarily mean exclusion. Dr. Elmasry does not advocate for every mosque to follow NBIC’s lead. At one of the dhikr gatherings—a core mystical practice of the Sufis—I attended, Elmasry addressed this directly: “Don’t say this mosque doesn’t do so-and-so activity, so it is not as good. In our tradition, we respect the range of opinions within the established orthodoxy. We may say ‘we have a different opinion,’ but we do not say ‘you are wrong.’” His statement is a telling one—he is not advocating an anything-goes pluralism but rather defending differences that remain within the boundaries of classical Islamic orthodoxy.

Shifting Equilibrium

Despite their distinct identities, these institutions remain deeply interconnected. I have been a regular ISCJ attendee but chose to have my wedding at MCGP. The president of NBIC’s board sends his kids to the ISCJ school. The imam of the nightly Ramadan prayers at ISCJ attends dhikr gatherings at NBIC.

But the equilibrium is shifting. NBIC’s success is influencing its neighbors, directly and indirectly. Dr. Elmasry’s wife now serves as the principal of the full-time school attached to ISCJ, where students are introduced to the principles of Islamic jurisprudence. Recognizing its waning appeal among young adults, ISCJ recently hired a new resident scholar, Shaikh Ismail Bowers, a widely respected Oxford PhD candidate and seminary-trained scholar. After attending a dhikr gathering at NBIC, Bowers attempted to discuss its value at ISCJ the next day— only to be met with resistance. An audience member insisted that collective dhikr constitutes a forbidden religious innovation. This moment encapsulates the constraints ISCJ faces: even as it welcomes dynamic young leadership, it remains answerable to a broad base of congregants with limited exposure to traditional Islamic scholarship. How Bowers navigates this tension will be revealing. Will ISCJ evolve into a site of deeper engagement led by the resident scholar, or will it remain a consensus-driven institution, serving as a broad, low-barrier entry point for the community?

Conclusion: Looking Ahead and Outside

The Muslim immigrants who moved to the tri-state area did not expect, or even encourage, their children to pursue seminary studies. I don’t want to overstate how many second-gen immigrants are making this choice. But I do want to emphasize who is making it. These are high-achieving students and professionals who are taking gap years after undergrad, dropping out of medical school, or quitting lucrative jobs to immerse themselves in Islamic scholarship across the world.

NBIC has strong ties to Tarim, Yemen, but Rutgers graduates have also set out for Turkey, Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Pakistan, and Jordan. Several of them, men I once knew from our Islamic school, tell me their pursuit of advanced religious study is not an extension of their grade-school education but a reaction against it. The diluted, Greatest Common Factor Islam taught in our school was intellectually unconvincing. Some students were turned off from the faith altogether. But these men discovered the discursive Islamic tradition later, in college—just as the American ideological landscape was hardening into reactionary politics and dogmatic activism. That discovery animates their intellectual appetite today, precisely because it offers coherence and meaningfulness outside those binaries.

The NBIC community has found a way out of Greatest Common Factor Islam without turning to ideological extremism. Their Islam is neither a liberal reformation that dilutes theology to accommodate modern sensibilities, nor is it a fundamentalist rejection of the contemporary world. It is also not the Islam of their parents, or a diasporic “return to our roots” campaign. Instead, it connects to a specific lineage of centuries-old discourse that offers a framework for engaging with modernity without surrendering to it. While NBIC and Dr. Elmasry have become the most visible faces of this revival, they are part of a broader ecosystem. Quietly, other traditionally trained scholars, like Mufti Bilal Mohammed and Mawlana Mateen Khan, have been contributing to this intellectual culture for years, especially amongst Rutgers students. Together, these parallel efforts are expanding the reach of classical Islam beyond any single mosque or institution.

Their Islam is neither a liberal reformation that dilutes theology to accommodate modern sensibilities, nor is it a fundamentalist rejection of the contemporary world.

Against America’s backdrop of religious decline and cultural transformation, this story is special. The decline of traditional religious practice hasn't created a purely secular society but rather one where political ideologies function as quasi-religions. Everyone operates from some kind of theology, even when it's secular. The woke fixation on systemic injustice, the MAGA creed of American victimization, the techno-optimist faith in innovation—each promotes a cosmology with its own creation stories, moral imperatives, and visions of redemption. In this context, classical Islamic scholarship offers American Muslims a cosmology that exists upstream of our fractious political debates.

Dr. Elmasry’s ambitions are bold. He envisions NBIC as a future global center of Islamic learning, with English as its medium. They are building it, and people are beginning to arrive.

[1] I focus on boys and men here only because mosques are gender segregated. American mosques are actually quite inclusive for women, especially compared to mosques in parts of the Islamic world.

[2] For an academic discussion of “Islam as a discursive tradition” see Anjum, O. (2007). Islam as a Discursive Tradition: Talal Asad and His Interlocutors. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27(3), 656-672. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/224569.

[3] For an accessible but comically orientalist profile of Dar al-Mustafa and its founder, Habib Omar bin Hafiz, see this profile by the New York Times.

[4] There are mosques and institutions beyond the ones I focus on here—some of which I am simply less familiar with. For example, the Central Jersey Institute for Islamic Studies (CJIIS), an influential Deobandi-oriented seminary, happens to occupy office space above my favorite Thai restaurant, and shares a hallway with a Pilates studio and a weed dispensary.

ASA. I’ve been in the central Jersey ecosystem for the last 20 years and have seen this development before my own eyes. I used to go to NBIC when it was a single curtained room and now I bring my kids there.

The real gem of this place is the leadership of the scholars and people of ilm. May God elevate them and keep us close to centers of knowledge like this.

“(nbic] connects to a specific lineage of centuries-old discourse that offers a framework for engaging with modernity without surrendering to it. While NBIC and Dr. Elmasry have become the most visible faces of this revival, they are part of a broader ecosystem. “

Well done!

Great read, thanks